When Archaeology Met Geology: The Pottery That Rocked Acadia’s World

It’s 8 am and you’re 20 years old. As you take a sip of unbelievably strong, hot coffee—maybe ill-advised before a day in the blazing Grecian sun—you pull on your long pants to protect you from the thorns that rip bare legs apart, lace up your hiking boots, and pack your bag for a day of archaeological exploration on the Mani Peninsula.

On May 26, after three weeks of exploring your 0.5 km2 survey area, the hour-long drive from your hotel up and down switchbacks to your work site is now familiar to you. Though you know where you’re heading for the day, what you don’t know is what you’ll uncover as you dig into the past.

Much less do you expect to discover a phenomenon that you hadn't imagined even possible.

Mapping the Mani Peninsula

In summer of 2025, 15 members of an interdisciplinary crew, including Acadia students Bella MacQuarrie (Msc Geology) and Cameron Barnard ('25), embarked on a trip to southern Greece to work on the Southern Mani Archaeological Project (SMAP) led by Dr. Chelsea Gardner (History & Classics) Dr. Bill Parkinson (Field Museum, Chicago).

The project, funded by a SSHRC Insight Grant, aims to enrich our understanding of the past and current life in the Mani peninsula.

In the first systematic, scientific, and comprehensive archeological investigation in the region, Dr. Gardner’s team is working to map how remote communities identified, connected, and interacted in the Mani peninsula of Greece across human history.

Basically, they went in with the broad question of “what was going on here?” Then, Dr. Gardner explains, they can start narrowing in, asking questions like who were these people, who did they interact with, and what were their settlement patterns?

Part of understanding the human history of the peninsula is understanding the land itself. Dr. Gardner enlisted Dr. Mo Snyder (Earth and Environmental Science) and their student, Bella, to bring their geological expertise to the team. The geological surveys of the area are outdated, as the most recent map was produced in 1984. This map (as is the case generally for geological maps) is missing elements key to understanding the archaeological history of the peninsula, such as the location of marble outcrops that the ancient Greeks and Romans exploited for their rich colours.

“Archeology and geology are so intertwined, but it isn’t common practice to have a geologist on an archaeological team,” says Dr. Gardner. “That alone makes the project that much more rewarding and we’re learning so much more.”

What do rocks have to do with people? Or, why bring geologists on an archaeological survey?

Understanding the geology of the Mani Peninsula is an important piece of getting a full picture of the cultural landscape.

The rocks of the peninsula are largely limestone that have been altered through karstification. As that limestone dissolved over the millennia, caves and caverns were formed in which early humans made themselves at home. The peninsula has important archeological sites dating back as far as the paleolithic and neolithic eras, which makes the area crucial in understanding the early history of our species.

For the Greeks, the peninsula has always been culturally important. Likely due to the abundance of caves and the fact that it’s a barren, isolated area—it's the southernmost tip of Europe—it held particular significance. The southernmost point of the peninsula, at the site of Tainaron, was said to be the location of the entrance to Hades, the ancient Greek Underworld.

There are also large deposits of marble across the peninsula, none of which have been included in previous geological maps, that have been quarried since the Bronze Age (2,000s BCE). “People have been visiting the peninsula to extract coloured marble for millennia,” says Dr. Gardner. “The Romans especially got into it.”

So much of the way that people have lived on Mani has been informed by its geology. “That’s part of the intersection between geology and archaeology: the people we’re studying were interested in geological resources.”

The eras tour: pottery’s version

As the team made their way from the coast, up the mountain to the road marking the end of their survey area day by day, they found hundreds of pottery sherds. Because of all the modern building activity in the area and the difficulty of the terrain, they had at best hoped for a few concentrated scatters where the ground was visible. But the sherds they found were more in number and variety than they had ever anticipated.

The pottery sherds included fragments spanning roughly 2,000 years, according to preliminary analysis, from Neolithic, Classical, Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, and early modern eras.

Typically, as the centuries pass, new settlements are built over the old ones. Basically, archeologists usually find newer evidence of human life on top of the really old stuff. For instance, material from 1,000 CE would usually be on top of material from 500 CE, and so on, back through all of human history.

“The majority of diagnostic pieces (such as rims, bases, handles, and glazed pieces) were found in concentrated areas, such as around buildings, above the beach, and under over-hanging rocks,” explains Cameron. “The pattern possibly suggests that these ceramics had washed down from higher up the mountain, where buildings or a settlement could have been.”

“To see so many different time periods hanging out on the surface was really interesting,” she says. “That’s what got us: not just the amount, but that it was diachronic, or representative of multiple time periods, and all right there.”

The team was absolutely blown away by what they were finding, sure that this would be the highlight of the summer’s fieldwork.

Then came May 26.

The pottery that rocked their world

On that May morning as the team neared the top of their survey area at the road, they encountered something strange. Back in the eighteenth or nineteenth century, someone built a house on top of the dissolved and eroded rock surface, creating a natural basement. Despite every generation having added something to the complex (it now boasts concrete features, metal, and a satellite dish), it is abandoned and overgrown.

Ever the curious, intrepid crew, they trekked through the thick brush that makes up the latest additions to the complex’s landscaping and entered the makeshift, open-air basement.

They found a trapdoor leading from the lower level of the building to the makeshift basement, which had clearly been used as a garbage dump in recent history. But scattered amongst the trash were pieces of pottery. And like the pottery further down the mountain, it was from all different eras, but here there was even more of it, and in larger pieces.

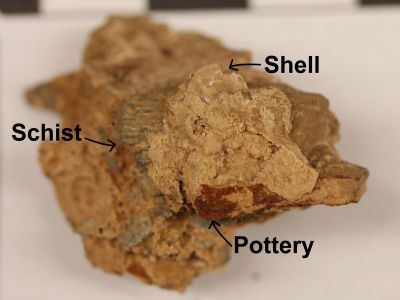

When they managed to tear their eyes away from the treasure trove of pottery on the ground, they noticed something odd. The sedimentary rock that formed the walls of the basement was actually made up of bits of pottery.

“We lost our minds when we found it!” says Dr. Snyder. “I have never heard of this happening before."

“It’s super bizarre and we don’t know how to explain it,” says Dr. Gardner.

Being scientists, of course they have a theory: A huge pocket of material got caught with a bunch of water in the gap underneath the house before it was built. Then as time passed, rock formed, incorporating the pieces of pottery into the rock itself.

“It’s not very water-rich so when it does rain it can move a lot of material,” explains Dr. Snyder. “So, if there’s one really big rainy day it can wash down a ton of stuff loose on the surface. It all accumulated in one area that was formed because the rocks had dissolved. All that stuff filled in the big hole and then people built a house on it.”

Remember all that limestone that the peninsula is made up of? It dissolves easily (hence the caves) and over time the dissolved material creates new rock. In this case, new rock with pottery sherds in it.

As a result, human history is now literally incorporated into the geological history of the Mani peninsula.

Dr. Snyder explains that while there are rocks with bits of plastic in them formed on present day beaches, beach rock is loose and crumbly. What the team found in Greece was, as Dr. Snyder describes it, “a rock rock. It’s more solid and it won’t crumble.”

“People joke about how in the future there will be sedimentary rocks with garbage in them,” says Bella, “but that’s literally what happened here.”

Teamwork makes the fieldwork dream work

Incredible discoveries like the pottery rock are what can happen when people with different expertise come together.

“Neither of our teams would have truly appreciated how weird this pottery rock was if we hadn't been there together,” explains Dr. Gardner.

“If I had gone to Mani as just a geologist I wouldn’t have even gone in the house because I’d be like ‘oh, that’s a house, I don’t care,’ and Chelsea might not have known what she was looking at with the rock,” says Dr. Snyder.

“That speaks to the importance of interdisciplinary teams and lots of people with deep expertise in different areas,” adds Dr. Gardner.

Having expert team members from many different fields also allowed the students to try their hand at new skills and learn from the best of the best in other, adjacent disciplines.

“The greatest experience I had on this trip was being exposed to experts in different fields,” says Cameron. “I got to experience other aspects of archaeology that I hadn’t been exposed to before, and I got to try things that were skills I never expected to get to do.”

“A strong team that works well and balances out other aspects of what others may lack is really helpful. And that comes inherently with an interdisciplinary team,” Cameron explains. “I got to have conversations with other people that have knowledge that rounded me out not just as an academic and professional but as a person as well.”

While the experience for Bella, Cameron, and their fellow researchers was certainly one-of-a-kind in its own way (who else can say they discovered a pottery rock?!), it’s common practice at Acadia.

“The great thing about Acadia is that in our department you get the opportunity to do so much outdoor fieldwork because it’s a small institution,” says Dr. Snyder. They recall that during their undergraduate degree at a large institution, they got out in the field one time. Whereas during the classes they run in Acadia’s geology department, their students get out three to five times per term.

“Getting people excited for fieldwork is my favourite part of the job, and Acadia does both a good job promoting that then actually delivering on it.”

And now, Bella and Cameron will get the chance to pass on this gift. The next step for them, says Dr. Gardner, will be having them step up to train the next students who come into the field with them.

"Sharing of knowledge. That’s what it’s all about. Empower students to have that knowledge and put them in positions to share it."

An ending

After driving back to the hotel, you go up to your room to clean up from your daily post-work dip in the ocean. Once you’re presentable, you head to your makeshift HQ in the lobby where the rest of your team is trickling in. One of your colleagues is playing guitar, and you see the pottery expert cataloguing sherds. You decide that tonight is as good a night as any to learn a new skill, so you ask if you can help out.

A few hours later with a belly full of tzatziki, feta cheese, and olives and a new skillset acquired, you aren’t sure if you’ll have the worst sleep of your life or the greatest. You don’t know yet how the excitement of discovery will weigh against the exhaustion of a long day in the field. But you do know that if you keep going out in the field, you’ll get the chance to find out all over again.